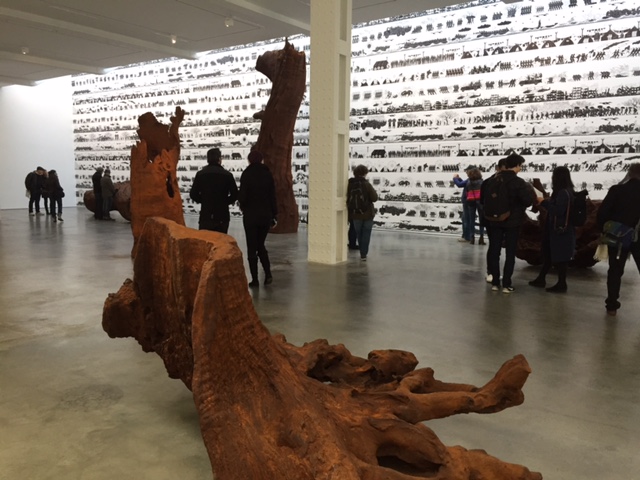

A tree grows in Chelsea at the Lisson Gallery (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

2016: ROOTS AND BRANCHES

Lisson Gallery

504 West 24th St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Mary Boone Gallery

541 West 24th St., 745 Fifth Ave. between 57th & 58th Sts.

AI WEIWEI: LAUNDROMAT

Deitch Projects, 18 Wooster St.

Through December 23, free

aiweiwei.com

This past October, Chinese dissident artist and activist Ai Weiwei swept into New York City, giving a talk at the Brooklyn Museum and opening four gallery exhibitions. He had been banned from international travel for four years since his March 2011 arrest and disappearance, and didn’t receive his passport back until July 2015. So it should not be surprising that the works deal with issues of home and planting roots, particularly in relation to the current refugee crisis around the world. At Lisson Gallery, one of three parts of “Ai Weiwei 2016: Roots and Branches” features giant, rusting cast-iron tree trunks and roots, creating a kind of dying forest, surrounded by black-and-white wallpaper depicting friezes of armed soldiers, explicitly referencing warriors on Ancient Greek black-figure vases; the same archaizing style is applied to modern military vehicles hovering around tent cities and rounding up men, women, and children; storms raging above dangerously overcrowded boats; people being carried away on stretchers; and signs on barbed-wire fences proclaiming, “No One Is Illegal,” “Open the Border,” and “#SafePassage.”

Ai Weiwei’s “Tree” rises up at Mary Boone in Chelsea (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

At Mary Boone in Chelsea, Ai has planted “Tree,” a twenty-five-foot-high twisting tree composed of parts of dead trees bolted together to form something new, a totem that evokes how every person is made of DNA from different cultures and traditions (as well as, of course, much of the same DNA). It’s an imposing structure standing in front of gold-and-white wallpaper showing elegant, circular patterns of surveillance cameras. Also on view are a Warhol-like self-portrait and a triptych of Ai’s famous “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn,” both made using LEGO pieces like pixels, in addition to “Treasure Box,” a large, wooden box resembling a Chinese puzzle.

Ai Weiwei’s “Spouts Installation” gives the finger to China’s past (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

At Mary Boone’s Midtown location, “Spouts Installation” consists of forty thousand ceramic spouts broken off from teapots dating from the Song to Qing dynasties, fracturing China’s past. Kaleidoscopic gray-and-white wallpaper features arms giving the finger, referencing Ai’s “Fuck Off” series, in which he takes photographs of himself flipping the bird in front of historical landmarks around the globe. The juxtaposition also makes the spouts, arranged in a circle around a central pole that is like a tree, look like a shadowy graveyard of broken middle fingers that have been silenced while also recalling Ai’s “Sunflower Seeds” installations at the Tate and Mary Boone in Chelsea. In the back room are the wooden box “Garbage Container,” the porcelain doormat “Blossom,” a glass-encased “Set of Spouts,” and the porcelain “Free Speech Puzzle.”

Ai Weiwei explores the refugee crisis in “Laundromat” at Deitch Projects (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Finally, at Deitch Projects in Soho, “Ai Weiwei: Laundromat” is a large room filled with racks of clothing, rows of shoes, stills from new films lining the walls, social media posts on the floor, a documentary video, and Allen Ginsberg’s poem “September on Jessore Road.” (“Millions of fathers in rain / Millions of mothers in pain / Millions of brothers in woe / Millions of sisters nowhere to go.” Inspired by the conditions at the Idomeni refugee camp on the Greek-FYROM border, the Shariya refugee camp in Iraq, and the Moria refugee camp in Lesbos, Ai has sought to give voice back to these refugees, who are suffering through war and extreme poverty; there is a deeply personal aspect to the work, as Ai’s family was sent to a labor camp when he was a child because his father was a poet and political dissident. The clothing and shoes are the real items worn by Syrian refugees at Idomeni — it’s particularly haunting seeing the racks of children’s clothing and rows of kids’ shoes — now properly cleaned instead of caked with mud and filth, each one individually tagged, as if offering each man, woman, and child a clean, new start, with renewed dignity.