Nicole Eisenman, “Coping,” oil on canvas, 2008 (courtesy the artist; Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin; and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: © Carnegie Museum of Art)

New Museum of Contemporary Art / Anton Kern Gallery

235 Bowery at Prince St. / 532 West 20th St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Through Sunday, June 26, $16 / through Saturday, June 25, free, 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

212-219-1222 / 212-367-9663

www.newmuseum.org

www.antonkerngallery.com3

In her foreword to the catalog for Nicole Eisenman’s first New York museum survey, New Museum director Lisa Phillips writes, “Nicole Eisenman is one of the most important painters of her generation and a vanguard voice in defining what figurative painting is today.” Bold words indeed, but “Nicole Eisenmann: Al-ugh-ories,” running at the New Museum through June 26, and “Nicole Eisenman: Magnificent Delusion,” continuing at Anton Kern Gallery in Chelsea through June 25, go a long way toward supporting that claim. The Scarsdale-raised, Brooklyn-based painter, sculptor, and installation artist has been part of the New York City scene since the 1990s; in fact, in 1994 she was included in the New Museum’s “Bad Girls” show, along with Matt Groening, Guerrilla Girls, Carrie Mae Weems, Lynda Barry, and others. Eisenman’s canvases mix art history and autobiography to tell intriguing stories that demand extended viewing not only to revel in her remarkable skill with color and a brush but to let the allegorical narratives unfold before you. At the New Museum show, pieces reference Philip Guston and Paul Gauguin, Giorgio di Chirico and Edvard Munch, Edouard Manet and Pieter Bruegel, Hans Holbein and Pablo Picasso and others, in a style that evokes classic paintings as well as German Expressionism and underground comics and zines.

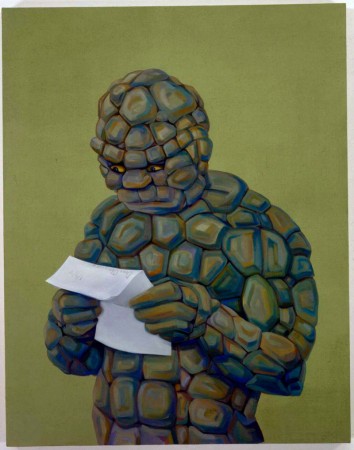

Nicole Eisenman, “From Success to Obscurity,” oil on canvas, 2004 (Hall Collection; photo courtesy New Museum)

In “From Success to Obscurity,” a character based on the Thing from the Fantastic Four is reading a letter that is addressed, “Dear Obscurity.” In “Commerce Feeds Creativity,” a shirtless man in a bowler hat holds out a spoon to a drooling, wounded woman tied up with wire so her bare breasts are squeezed into painful positions, the background unfinished, as if Eisenman is being forced to complete her work at the behest of a patriarchal capitalist market. In “Biergarten at Night,” a motley crew of men and women, many coupled, are drinking and smoking in the midst of a dark forest; near the center, a skeleton and a genderless person embrace like the man and woman in Munch’s “The Kiss,” while an oddly placed wire with halo-inducing lightbulbs droops across the middle of the canvas. Eisenman depicts herself at work in “Progress: Real and Imagined,” her studio adrift at sea, the artist hunched over in the center, drawing with a quill pen, an engaging counterpart to her sculptural installation of a table in her studio, in which the artist’s foot is hanging upside down from a crosslike object, most of her body in a bronze container.

“The Triumph of Poverty,” oil on canvas, 2009 (collection Bobbi and Stephen Rosenthal, New York; photo courtesy New Museum)

Eisenman also imbues her work with sociopolitical statements both overt and subtle. In “The Triumph of Poverty,” a group of downtrodden, zombielike people are gathered in and around a car with no doors or windows, fire peeking out of a chimney in the background, all looking off to the left, not exactly expecting that prosperity awaits. Among them are a man in a tuxedo whose pants have fallen down, revealing that his buttocks are where his genitals should be, making him an ass-backward leader; a child holding out a bowl, as if Oliver asking for more food in Oliver Twist; and a small black child with an extended belly, being led by an ominous white hand. In “Tea Party,” a bedraggled and defeated Uncle Sam slumps in a chair in an underground bunker stocked with gold bars, water, and canned food; meanwhile, a barefoot, longhaired man sleeps quietly, clutching his beloved rifle, while two other men are building an explosive device. The pièce de résistance is 2008’s “Coping,” in which a strange cast of characters wade through a thick river of feces in a European town in which Eisenman brings together the past and the present with a bevy of wonderful details, from a street-vendor coffee cup to lush green hills, from an overturned car to a waitress serving trays of beer, from clouds of shit to a green parrot sitting atop a cat’s head, from a woman clutching her dog to a mummy walking away. (The parrot and mummy show up in other works as well.) In the middle of it all, a naked woman, perhaps the artist herself, is wondering what comes next. It’s a glorious tour de force that shows much of what Eisenman has been working on the past few decades.

Nicole Eisenman show at Anton Kern takes direct aim at the viewer (photo courtesy Anton Kern Gallery)

In a catalog interview with New Museum artistic director Massimiliano Gioni and assistant curator Helga Christofferson, Eisenman notes, “I like the idea of documenting, of saving something for a future time. It’s a hopeful act. I also love this fucked-up city.” You can get a glimpse of what comes next, of the future, in her thrilling show at Anton Kern, featuring a small collection of spectacular paintings from 2015-16, many of which deal with communication in the modern world; a wall of playful drawings and watercolors from 1995 to the present; and another studio-based sculpture. In “Subway 2,” a G train is approaching as a man in the foreground looks down at his cell phone, a woman’s foot extends ever-so-slightly onto the yellow line at the edge of the platform, and straphangers in the background turn ghostly the farther away they are; Eisenman globs thicker, abstract splotches of paint on the closer tracks while making gorgeous use of color, from the blue on the man’s coat to the green stanchions to the yellow safety line and rainbow stairs in the distance. In “Weeks on the Train,” Eisenman depicts her friend, writer and performer Laurie Weeks, on a commuter train, working on her laptop, a cat in a carrier next to her, a German Expressionist man asleep in the row in front of her, next to a Guston-like big-eyed character peering out the window.

Nicole Eisenman, “Subway 2,” oil on canvas, 2016 (photo courtesy Anton Kern Gallery)

In “TM and Lee,” a pair of women relax in a landscape simultaneously referencing a beach and fertile croplands; one woman holds her knee, artlessly revealing her crotch, listening to a larger woman play a guitar. In “Long Distance,” another relaxed couple chat over the internet, their bodies in unusual positions that are at first hard to decipher. In “Morning Studio,” two lovers are on a futon, one of them looking possessively at the viewer; in the foreground is a can of tuna being used as an ashtray, while in the background is a projection of the generic Apple desktop galaxy next to a window revealing the blue sky, contrasting technology and reality. The show is also very much about the act of seeing, with eyes being a central repeated image. In “Droid,” an android’s left eye resembles an egg. In “Subway 2” and “Weeks on the Train,” oversized eyes demand attention. And in “Shooter 1” and “Shooter 2,” guns are aimed right at the viewer, the barrel of the gun serving as the shooters’ right eyes, powerful statements in lieu of the intense fight over gun control in the United States. Meanwhile, in the watercolor and graphite drawing “Cap’n ’Merica,” the sad superhero has given up, hitting the road like a penniless drifter. Indeed, the shows at the New Museum and Anton Kern firmly establish that Eisenman is one of the most important, and finest, painters of her generation.