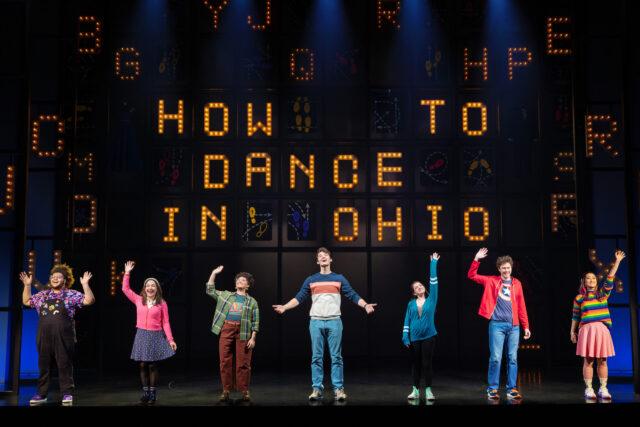

A jubilant cast lifts Hell’s Kitchen at the Public Theater (photo by Joan Marcus)

HELL’S KITCHEN

Newman Theater, the Public Theater

425 Lafayette St. at Astor Pl.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 14, $175

publictheater.org

Hell’s Kitchen, heading from the Public to the Shubert — it ends its run downtown January 14 and starts previews on Broadway on March 28 — (mostly) succeeds where New York, New York failed. Both stories take place in the city, use stage scaffolding to replicate fire escapes, follow the relationship between a man and woman involved in music, and are built around a hugely popular hit song about New York.

The latter, based on Martin Scorsese’s 1977 film, declares, “If I can make it there, I’d make it anywhere,” while the former proclaims that New York is a “concrete jungle where dreams are made of / There’s nothing you can’t do / Now you’re in New York!” But where New York, New York felt like a miscast movie shot in Toronto, Hell’s Kitchen, inspired by the life of Alicia Keys (who wrote the music and lyrics), has a far more legitimate feel, a more “empire state of mind,” flaws and all.

Maleah Joi Moon makes an explosive professional debut as Ali, a seventeen-year-old girl living with her extremely protective single mother, Jersey (Shoshana Bean), in a “one-bedroom apartment on the forty-second floor of a forty-four-story building on Forty-Third Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues, right in the heart of the neighborhood some people know as Hell’s Kitchen.” The building is filled with artists, including a trumpeter on thirty-two, a dance class on twenty-seven, opera singers on seventeen, poets on nine, painters on eight, a string section on seven through four, and a gospel pianist in the Ellington Room on the ground floor.

It’s summer in the 1990s, and Ali has decided it’s time for her to get busy with the older Knuck (Chris Lee), who drums on buckets in the street with his friends Q (Jakeim Hart) and Riq (Lamont Walker II). Ali and her homegirls, Jessica (Jackie Leon) and Tiny (Vanessa Ferguson), are sure the men are “up to no good,” but as Ali says, “We need that trouble in our lives.”

Knuck (Chris Lee) and Ali (Maleah Joi Moon) find themselves in trouble in Alicia Keys musical (photo by Joan Marcus)

That’s the last thing Jersey wants for her daughter, so she enlists her besties, Millie (Mariand Torres) and Crystal (Crystal Monee Hall), and jovial doorman Ray (Chad Carstarphen) to keep an eye on Ali’s comings and goings. Jersey does not want what happened to her — an early, unwanted pregnancy by an unreliable man, a jazz musician named Davis (Brandon Victor Dixon) — to happen to her stubborn daughter.

As she prepares for her potential sexual awakening, Ali becomes intrigued by Miss Liza Jane (Kecia Lewis), the elderly woman who plays the piano in the Ellington Room and soon becomes Ali’s mentor. But the trouble that Ali soon encounters is not the trouble she needs.

Hell’s Kitchen is structured around two dozen Keys songs, from such albums as 2001’s Songs in A Minor, 2003’s The Diary of Alicia Keys, 2007’s As I Am, 2012’s Girl on Fire, 2020’s Alicia, and 2021’s Keys, and three new tunes written specifically for the show, “The River,” “Seventeen,” and “Kaleidoscope.” The orchestrations by Tom Kitt and Adam Blackstone are lively, and Camille A. Brown’s choreography captures the energy of the street on Robert Brill’s set, enhanced by projections of the neighborhood by Peter Nigrini. The naturalistic costumes are by Dede Ayite, with effective lighting by Natasha Katz and sound by Gareth Owen.

The show is directed with a vibrant sense of urgency by Tony nominee Michael Greif (Dear Evan Hansen, Next to Normal), but the book by Kristoffer Diaz (The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity, Welcome to Arroyo’s) languishes in clichés, including several cringey scenes that don’t feel real, creating a choppy narrative that doesn’t flow like Keys’s music.

Moon is magnetic as Ali; you can’t take your eyes off her for even a second. Tony nominee Bean (Mr. Saturday Night, Waitress) is engaging as the overwrought mother, shaking things up with “Pawn It All,” while Obie winner Lewis (Dreamgirls, Ain’t Misbehavin’) nearly steals the show as Miss Liza Jane, channeling Maya Angelou when she says such lines as “I will not allow you to let the pain win,” then bringing down the house with “Perfect Way to Die.” Lee (Hamilton) has just the right hesitation as Knuck, acknowledging the obstacles he faces every step of the way, and Carstarphen (Between the Bars, Neon Baby) is eminently likable as the adorable doorman.

In the last nine years, the Public has seen a bunch of shows transfer to Broadway, with differing levels of success (Hamilton, Fun Home, Ain’t No Mo’, for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, Fat Ham, and Here Lies Love, with Suffs coming in April). With some significant tweaking, Hell’s Kitchen has the chance to be both a critical and popular hit on the big stage.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]