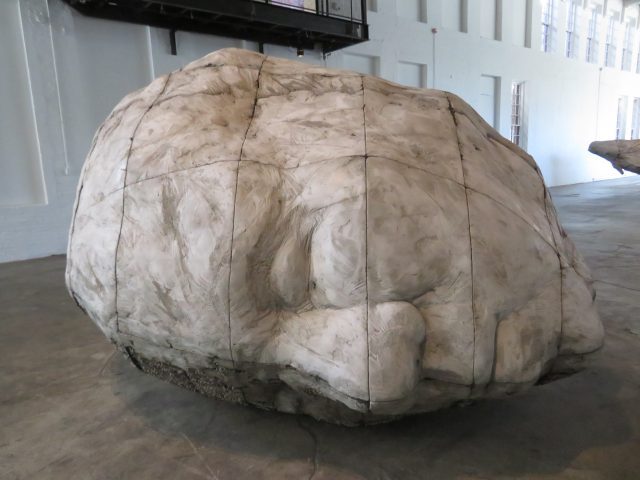

Ledelle Moe’s “When” consists of giant hollow heads across the floor and tiny ones on back walls (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

MASS MoCA

1040 MASS MoCA Way, North Adams, MA

Wednesday – Monday, $8-$20 timed tickets in advance, 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

www.massmoca.org

With New York City museums opening up again, we decided to prepare by heading up to the Berkshires to visit MASS MoCA and the Clark Institute, both of which began welcoming visitors post-pandemic lockdown the second week of July. We used the trip as sort of a test case, examining how they were doing things to gauge our approach to arts institutions here in the five boroughs. In our opinion, they are doing everything right, so rent a car and get up there as soon as you can.

At MASS MoCA, a repurposed industrial complex in North Adams with more than one hundred thousand square feet of gallery space indoors and outdoors that opened in 1999, one must order timed tickets in advance; we showed up twenty minutes early but were told nicely that we would have to wait. We spent some of that time looking at Gamaliel Rodríguez’s sixty-foot-long mural La travesía (“Le voyage”), which equates the architecture at MASS MoCA with that of his native Puerto Rico and other locations, in an eye-catching purple tint, which you can see for free by the store and the café (where you can get freshly made lemonade and a killer BLT).

Jarvis Rockwell’s Us is a parade of fun figurines (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Ticketholders line up outside to enter the museum; the now ever-present dots keep everyone at a distance of six feet. Once inside, communing with the art feels completely safe, as the number of visitors is kept small and most of the galleries are vast and wide open. At times we were the only ones in a space (save for a museum employee or two), and at other moments, even if there were a dozen people in the same gallery, we were all extremely far away from one another. (In addition, everyone was aware of social distancing, so there was never any crowding, as we all were respectful of the situation, and everybody wore a mask, over their mouth and nose.)

It’s nearly impossible to experience any of the art without thinking about the Covid-19 crisis, even if it was made long before that. The centerpiece exhibit, on view through January 3, is Ledelle Moe’s “When,” which consists of fragile-looking colossal heads and bodies that are actually made of weathered concrete, many lying on their sides, with hollow insides you can peer into. The installation is particularly meaningful given the current movement of taking down monuments and statues; on the far wall and upstairs are hundreds of tiny heads that are like the twitterverse commenting on the sight or another group of the displaced, relegated to the background.

Blane De St. Croix’s “How to Move a Landscape” (through September 2021) is a breathtaking collection of environmental works that don’t bode well for the future of the planet. Moving Landscapes is a miniature train in which each car carries a different kind of landscape, circling through two holes in the wall. Broken Landscapes is a miniature re-creation of the US-Mexico border where fencing has been put up; the piece is based on De St. Croix’s travels to fifteen border crossings. You can walk under Hollow Ground, a giant hunk of foam permafrost with holes in it; get up close and personal with Collapsing Pillar, a vulnerable tower that could seemingly fall at any moment; and get on your knees to look up and down at Alchemist Triptych, a trio of gold, silver, and copper tornadoes that decrease in diameter as they approach the floor, where you can look into a void going deep into the earth.

For “Amity/Enmity,” Massachusetts artist Ben Ripley repurposes images from the Field Museum’s 1933 exhibit “Races of Mankind,” which comprised more than a hundred anthropological sculptures by Malvina Hoffman, inspired by white nationalist Sir Arthur Keith, a leader in the scientific racism movement who announced the “amity-enmity complex,” which deals with human tribalism, racial segregation, and evolution. Ripley transposes images of himself over photographs and 3D scans of Hoffman’s sculptures, redefining them. He asks, “This historical example of the forceful authority of museums and the seductive power of beauty leading to visual arguments whose consequences we are only now starting to understand suggest an urgent examination of the responsibility of the visual arts on a larger scale. Are our museums leading to a fruitful exchange of diverse ideas? Is our visual art reductive and divisive or humanizing and complex? What are the future consequences of a pursuit of ideological purity? How can art be used to heal and persuade rather than create an exclusive echo chamber? Who do artists and museums serve?” Those are pertinent questions as arts institutions return amid a health crisis and protests about systemic racism.

ERRE re-creates border scenarios in his powerful multimedia installation (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

ERRE (Marcos Ramírez) also takes on the border dispute in “Them and Us” (“Ellos y Nosotros”) (through summer 2021), setting up a sample San Ysidro Port of Entry. ERRE, who splits his time between his native Tijuana and San Diego, offers visitors the choice of entering through two corridors, one marked “Us,” the other “Them.” The gallery contains such works as Toy-an Horse, the burned remains of his 1997 two-headed Trojan horse; colorful Eye Charts featuring quotes from Thomas Jefferson, US senator Dennis Chavez, Sitting Bull, and others; the video The Body of Crime (The Black Suburban), which reveals blatant corruption in law enforcement; Sing-Sing, an abstract iron cage with a bed inside; Orange Country, four orange prison jumpsuits hanging on a wall, representing a father, mother, and two kids, right next to The Cell, a jaillike solitary confinement structure; and Of Fence (which can be read as “offense,” a word with multiple meanings), a deteriorating, rusted corrugated-metal fence that separates the exhibit while referencing other types of physical and psychological separation.

Ad Minoliti’s “Fantasías Modulares” is a candy-colored wonderland (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Ad Minoliti’s “Fantasías Modulares” is a fantastical trip back to childhood, with adorably cute characters that feel like they have emerged from a candy-colored cartoon world where there’s no difference between humans, animals, and machines, no gender, race, class, or political gaps. Incorporating painting, sculpture, drawing, and installation, the artist, based in Buenos Aires and Berlin, creates an idyllic place to take a playful break away from an ever-more-challenging real world.

You need to reserve timed tickets (at no extra charge) for James Turrell’s “Into the Light,” a look at his Roden Crater project, several light sculptures, and the pre-socially-distanced Perfectly Clear (Ganzfeld), in which a half dozen people experience a heavenly, mesmerizing color-changing environment, and Hind Sight, a two-person-at-a-time journey into complete darkness.

Among the other must-see exhibits are Sol LeWitt’s “Wall Drawing Retrospective,” a small but tantalizing Louise Bourgeois sculpture show, several rooms of Jenny Holzer’s multimedia truisms, Sarah Oppenheimer’s S-334473 (ask the museum worker to operate them for you), Jarvis Rockwell’s Us parade of character toys and figurines, Barbara Ernst Prey’s “Building 6 Portrait: Interior” ultrarealistic paintings, Franz West’s outdoor Les Pommes d’Adam sculptures, and Joe Wardwell’s Hello America: 40 Hits from the 50 States, which was inspired by J. G. Ballard’s 1981 novel and uses quotes from Negativland’s 1991 song “I Still Haven’t Found Snuggles.” Unfortunately, long-term installations by Stephen Vitiello, Michael Oatman, Gunnar Schonbeck, and Anselm Kiefer are currently closed. Be prepared to spend a full day at MASS MoCA, as there is art everywhere, and you’ll feel safe every step of the way. In addition, the institution is hosting live outdoor concerts in the central courtyard, where the audience hangs out in large individual rectangles drawn on the ground; upcoming shows feature Marco Benevento on September 12 and June Millington on September 19.

Giuseppe Penone’s Le foglie delle radici (“The Leaves of the Roots”) greets visitors to the Clark (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

CLARK ART INSTITUTE

225 South St., Williamstown, MA

Tuesday – Sunday, $20 timed tickets in advance, 10:00 am – 5:00 pm

www.clarkart.edu

Since 1955, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute has been displaying the couple’s extensive, impressive collection, along with special exhibitions. It reopened in July and is doing a terrific job with its Covid-19 regulations; timed tickets are required, and every gallery has a limit of how many visitors are allowed in at any one time, from two to see Edgar Degas’s exquisite Little Dancer Aged Fourteen to eight in the museum shop to a maximum of twenty-five in the largest space; I’m not sure there were twenty-five people total in the museum when I was there. The permanent collection is an absolute joy, with paintings and sculptures by Winslow Homer, Frederic Remington, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Mary Cassatt, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jean-François Millet, Frederick William MacMonnies, Claude Lorrain, Édouard Manet, Giovanni Boldini, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Francisco de Goya, John Constable, and Berthe Morisot. Don’t miss Paul Gauguin’s strikingly yellow Young Christian Girl, George Inness’s glorious Sunrise in the Woods, John Singer Sargent’s unusual Fumée D’ambre Gris (Smoke of Ambergris), Claude Monet’s inviting The Cliffs at Étretat, Auguste Rodin’s frightening Man with Serpent, and J. M. W. Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights (Close at Hand) to Warn Steamboats of Shoal Water, which appropriately resides on a wall all by itself.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Model D Pianoforte and Stools is a highlight of the Clark collection (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Through December 13, you can catch “Lines from Life: French Drawings from the Diamond Collection,” containing more than forty chalk, crayon, graphite, charcoal, ink, and graphite works by Paul Cézanne, Eugène Delacroix, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Théodore Géricault, Odilon Redon, Degas, Millet, Morisot, Pissarro, and others, a gift from Herbert and Carol Diamond, longtime friends of the Clark.

Lin May Saeed, Thaealab, cast bronze, lacquer, hazelnuts, 2017 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Mexico City-based artist Pia Camil’s “Velo Revelo,” comprising three large-scale fabric sculptures, will be on view through January 3. But you’ll have to hurry if you want to see Lin May Saeed’s touching “Arrival of the Animals,” which continues at the Clark’s Lunder Center at Stone Hill through October 25, a brief walk or quick drive from the main building. The German artist explores the relationship between animals and humans in her work, which ranges from drawings and paintings to sculptures using such materials as steel and lacquer or polystyrene foam, plaster, wood, and cardboard. As you wander around the space, you’ll come upon a pangolin, a lion school, seven sleepers hiding in a cave to escape religious persecution, a panther, and, outside, a bronze thaealab, which is Arabic for fox. Saeed has also chosen works from the Clark to complement and inform her installation, including pieces by Niccolò Boldrini, Albrecht Dürer, Delacroix, and Géricault.

J. M. W. Turner, Rockets and Blue Lights (Close at Hand) to Warn Steamboats of Shoal Water, oil on canvas, 1840 (photo courtesy the Clark Institute)

As a major bonus, especially during this time of Covid-19, the Clark offers lots to see outside across its 140-acre campus. You can hike through a forest, linger by Schow Pond, walk across a grassy plain, sit under cross-bred trees, and climb up a hill while also enjoying art. When you first arrive, you’re greeted by Giuseppe Penone’s Le foglie delle radici (“The Leaves of the Roots”), a thirty-foot-high upside-down bronze tree with a living sapling growing out of the top, which can now be interpreted as a metaphor for the state of the country at this tense moment. The Clark’s first outdoor exhibition, “Ground/work,” has been delayed because of the pandemic, but Analia Saban’s Teaching a Cow How to Draw is already up, in which Saban has repurposed the long wooden split-rail fence that separates the museum from the outdoor grounds by adding “drawings in space” to the boundary, art lessons (including the Rule of Thirds and the Golden Ratio) meant not only for us but for the cows that live in the hills.

Thomas Schütte’s Crystal offers a respite and beautiful views of the grounds (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

You’ll also find William Crovello’s red granite Katana sculpture on the grass; four of Jenny Holzer’s white granite benches from “The Living Series” situated by the large pond (you can sit on them, but first read their ever-more-relevant messages, such as “It can be startling to see someone’s breath, let alone the breathing of a crowd you usually don’t believe that people extend that far”); and Thomas Schütte’s Crystal, an open, asymmetrical structure made of wood and zinc-coated copper near the top of Stone Hill where you can take a break and savor lovely views of the grounds, with no one around you, as if you have the world to yourself.

The Clark sets out very clear rules during Covid-19 crisis (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The Met, MoMa, the Morgan, the American Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the City of New York, and the Whitney are now open in New York, with the Guggenheim, El Museo del Barrio, the New-York Historical Society, the Cloisters, the Brooklyn Museum, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the New Museum, the Museum of Arts and Design, the Rubin, MoMA PS1, the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum, and others scheduled to do so in the coming weeks. One can only hope that their approach to reopening compares favorably to those of MASS MoCA and the Clark, which are doing everything right. Just remember to wear your mask, observe social distancing, wash your hands, and respect your fellow art lover.