Boy Blue returns to Lincoln Center with Blak Whyte Gray at Mostly Mozart Festival (photo by Carl Fox)

MOSTLY MOZART FESTIVAL

Gerald W. Lynch Theater at John Jay College

524 West Fifty-Ninth St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

August 1–3, 7:30

Festival continues through August 9

www.lincolncenter.org

boyblueent.com

London-based troupe Boy Blue’s Blak Whyte Gray consists of a trio of vibrant, electrifying works that fuse hip-hop, contemporary dance, and African movement while taking on the current state of sociopolitical tension in England, America, and the world. “Do we crack and break the system made for us? / rules give people purpose / can you tell them what they know is a lie?” Boy Blue cofounder, composer, and co-artistic director Michael “Mikey J” Asante asks in a poem printed in the program. “Inhale. Exhale. / You’re ALIVE / Wake Up / It’s REVOLUTION.” Blak Whyte Gray made its US debut last November at Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival, where it was such a hit that it’s back for a special return engagement at the Mostly Mozart Festival, continuing through August 3 at the Gerald W. Lynch Theater at John Jay College. It’s divided into three thrilling sections in which Asante and choreographer and director Kenrick “H2O” Sandy proceed from the subtle to the overt in making their case.

Michael “Mikey J” Asante and Kenrick “H2O” Sandy call for revolution in Blak Whyte Gray (photo by Carl Fox)

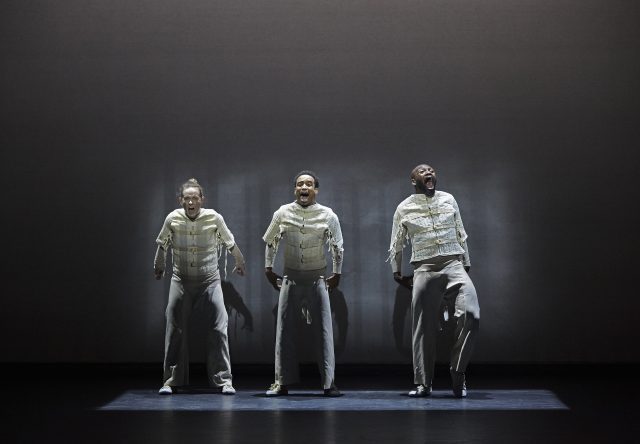

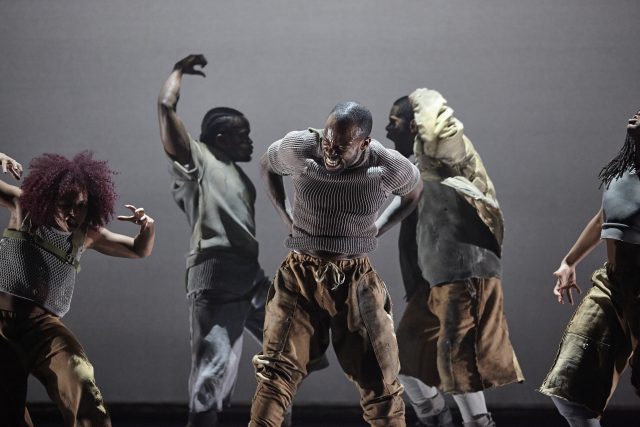

The evening begins with Whyte, with Gemma Kay Hoody, Ricardo Da Silva, and Nicole McDowall in white fringed dress that evokes both straitjackets and Japanese anime robots; the three dancers move like automatons, seemingly trapped in a white rectangular box, at one point their hands behind their backs as if handcuffed. On the screen behind them is projected a white box with black vertical lines that recalls a barcode or uneven prison bars; the barcode shows up again on the floor in a later piece. (The costumes are by Ryan Dawson Laight, the lighting by Lee Curran.) The dancers move as if controlled by rather than in response to the music, individually and in unison, eventually letting out silent screams. Gray opens with Theophillus “Godson” Oloyade, wearing a hooded winter jacket, sliding on his back onto the stage, soon joined by Natasha Gooden, Jordan Franklin, and others, incorporating hip-hop, African dance, and krumping as they rally together in an uprising, pointing unseen rifles and lobbing invisible hand grenades at the audience in a powerful statement of action rather than reaction.

Following intermission, the troupe returns for the scintillating Blak: A man falls to the ground, possibly dead, and is surrounded by others, who try to resuscitate him, lift him up, and get him to stand on his own. The community refuses to give up, and moments later they are wrapping him in an elegant red cloth, as if anointing him king, an indirect reference to Asante’s Ghanaian and Egyptian heritage, while masks descend paying tribute to their ancestors. The company, which also includes Dani Harris-Walters and Idney De’Almeida, is extraordinary, bold and physical, with exquisite control of their bodies. Blak Whyte Gray is an exhilarating experience, with a spectacular conclusion that is filled with hope for a new conception of individual and collective identity.