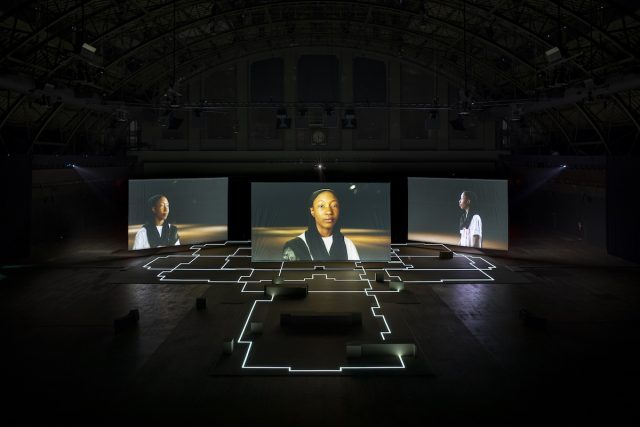

Drill is centerpiece of extensive Hito Steyerl exhibition at Park Avenue Armory (photo by James Ewing)

Park Avenue Armory

643 Park Ave. at 67th St.

Through July 21, $20

armoryonpark.org

“Spare no expense to make war beautiful,” historian Anna Duensing says in Drill, referring to military history. Drill, a three-channel, twenty-one-minute video, is the centerpiece of German artist Hito Steyerl’s site-specific, wide-ranging multimedia installation of the same name at Park Ave. Armory, where it continues through July 21. Projected on both sides of three large screens in the fifty-five-thousand-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall, Steyerl’s film delves into the history of the armory, from its time as the headquarters of the Seventh Regiment of the National Guard, known as a silk-stocking regiment, to its exclusive use by the wealthy and its direct relationship to the founding of the National Rifle Association. Steyerl goes to the armory basement, formerly a shooting range, where bullet holes can still be seen in the walls; includes clips of speeches by antigun activists at a Washington, DC, rally; and follows the Yale University Precision Marching Band as it makes its way through the drill hall, playing music by Jules Laplace based on data sonification from casualty statistics of AR-15 violence and mass shootings, with choreography by Thomas C. Duffy. Among the participants are Nurah Abdulhaqq of National Die-In, Kareem Nelson of Wheelchairs Against Guns, retired school principal and proud gun owner Judith Pearson, and gun violence prevention activist Abbey Clements. A series of interconnected bulbs on the floor occasionally light up in white and red, linking the viewer to what is happening onscreen.

In her 2013 e-flux article “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?,” Steyerl wrote, “Data, sounds, and images are now routinely transitioning beyond screens into a different state of matter. They surpass the boundaries of data channels and manifest materially. They incarnate as riots or products, as lens flares, high-rises, or pixelated tanks. Images become unplugged and unhinged and start crowding off-screen space. They invade cities, transforming spaces into sites, and reality into realty. They materialize as junkspace, military invasion, and botched plastic surgery. They spread through and beyond networks, they contract and expand, they stall and stumble, they vie, they vile, they wow and woo.” That statement relates to several of the other works in the show, spread throughout the armory’s period rooms and hallway.

Sandbags offer an uncomfortable place to sit while watching Hito Steyerl’s videos Duty Free Art and Is the Museum a Battlefield? (photo by James Ewing)

In the Parlor, Is the Museum a Battlefield? is an illustrated lecture projected on two screens and a box of white sand as Steyerl investigates the fascinating relationship between art museums and war, starting with a bullet that killed a friend of hers. The audience sits on sandbags, immersed in the narrative that involves the Louvre, the Hermitage, and other arts institutions. “Museums are of course battlefields. They have been throughout history,” she says. “They have been torture chambers, sites of war crimes, civil war, and also revolution.” Although the illustrated lecture was produced for the thirteenth Istanbul Biennial, it feels right at home at the armory, a building initially constructed for the military that now is an arts institution itself. That is followed by Duty Free Art, in which Steyerl delves into income inequality through art, business, and war via freeports, where collectors store their art holdings without having to pay taxes, impacting the global economy.

In the Veterans Room and Library, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, named for the five most-used English words in songs on the Billboard charts, features concrete and neon sculptures of those words along with video of product testing on robots, while Robots Today ties together narration from Muslim polymath Al-Jazari’s 1205 Automata with shots of a Kurdish city destroyed by the Turkish military in 2016.

ExtraSpaceCraft offers comfy chairs to watch the Iraqi National Observatory become the Autonomous Space Agency (photo by James Ewing)

Broken Windows is shown at both ends of the central hallway; one end depicts Chris Toepfer and other community activists painting canvases and placing them over broken windows in abandoned buildings in Camden, New Jersey, while at the other end researchers in London test the sound of breaking glass for artificial intelligence. The title of the video takes on added meaning here in New York City given the NYPD’s controversial use of broken windows policing, which believes that targeting smaller crimes will prevent bigger ones.

The show also includes The Tower in the Mary Divver Room and ExtraSpaceCraft in the Board of Officers Room, which are like watching virtual reality video games, while Prototype 1.0 and 1.1 in the Field and Staff Room is a pair of blue robots made of foam-and-aluminum, one standing, the other lying on the floor, as if they had come out of Hell Yeah We Fuck Die after undergoing brutal testing. And in the Colonels Reception Room, Freeplots offers hope for the future amid all the technological mayhem, a collaboration with El Catano Community Garden in East Harlem that consists of flowers blooming in wooden planters filled with horse-manure compost, turning the crates that store art in the freeports into something positive for everyone. The exhibition requires a significant investment of time and concentration; the works are complex, and the videos run more than two hours in total, but Steyerl has a lot to say that is worth paying attention to, even if some of the delivery is less inspiring than others. On July 20 at 3:00 and 5:00 ($10), there will be a performance lecture by Anton Vidokle, Adam Khalil, and Bayley Sweitzer, “The Dead Walk into a Bar,” which promises: “As a staff of identical ushers draws back layers of confusion and pain, the freshly resurrected gradually become aware of the reality of their corporeal reinsertion: perhaps the world of the living is not a world at all; to be alive in this place may merely be an exhibit.”