Maborosi, starring Makiko Esumi, kicks off six-film tribute to Hirokazu Kore-eda as appetizer to his latest, Shoplifters

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

165 West 65th St. between Eighth Ave. & Broadway

November 19-22

www.filmlinc.org

www.kore-eda.com

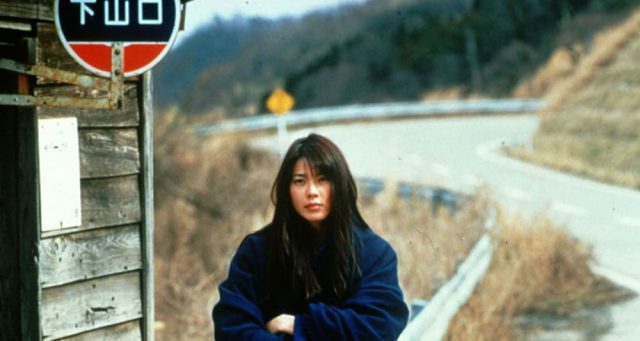

To celebrate the theatrical release of Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest work, Shoplifters, the Palme d’Or winner that opens November 23, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting six of the master’s earlier tales, concentrating on his exquisite depiction of family life. Running November 19-22, the mini-festival provides a terrific entry into the oeuvre of Kore-eda, a visionary who tells a story like no one else. “Six by Kore-eda” begins with his first fiction film, Maborosi, which followed three documentaries (Lessons from a Calf, However . . . , August without Him). After Yumiko’s husband, Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano), mysteriously commits suicide, she (Makiko Esumi) gets remarried and moves to her new husband’s (Takashi Naitō) small seaside village home with her son (Gohki Kashima), where she begins to put her life back together. This stunning film is marvelously slow-paced, lingering on characters in the distance, down narrow alleys, across gorgeous horizons, with very little camera movement by cinematographer Masao Nakabori. Maborosi, the only one of his films he didn’t write — the screenplay is by Yoshihisa Ogita, based on the novel by Teru Miyamoto — is a stunning debut from one of the leading members of Japan’s fifth generation. It is screening at the Walter Reade Theater on November 19 at 6:30 and November 22 at 9:00

To celebrate the theatrical release of Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest work, Shoplifters, the Palme d’Or winner that opens November 23, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting six of the master’s earlier tales, concentrating on his exquisite depiction of family life. Running November 19-22, the mini-festival provides a terrific entry into the oeuvre of Kore-eda, a visionary who tells a story like no one else. “Six by Kore-eda” begins with his first fiction film, Maborosi, which followed three documentaries (Lessons from a Calf, However . . . , August without Him). After Yumiko’s husband, Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano), mysteriously commits suicide, she (Makiko Esumi) gets remarried and moves to her new husband’s (Takashi Naitō) small seaside village home with her son (Gohki Kashima), where she begins to put her life back together. This stunning film is marvelously slow-paced, lingering on characters in the distance, down narrow alleys, across gorgeous horizons, with very little camera movement by cinematographer Masao Nakabori. Maborosi, the only one of his films he didn’t write — the screenplay is by Yoshihisa Ogita, based on the novel by Teru Miyamoto — is a stunning debut from one of the leading members of Japan’s fifth generation. It is screening at the Walter Reade Theater on November 19 at 6:30 and November 22 at 9:00

AFTER LIFE (WANDÂFURU RAIFU) (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 1998)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

Monday, November 19, 8:45

Thursday, November 22, 7:00

www.filmlinc.org

Kore-eda’s second narrative feature, After Life, is an eminently thoughtful film about two of his recurring themes: death and memory. Every Monday, the deceased arrive at a way station where they have three days to decide on a single memory they can bring with them into heaven. Once chosen, the memory is re-created on film, and the person goes on to the next step of his or her journey, to be replaced by a new batch of souls. The way station is staffed by guides, including Takashi Mochizuki (Arata), Shiori Satonaka (Erika Oda), and Satoru Kawashima (Susumu Terajima), whose job it is to interview the new arrivals and help them select a memory and then bring it to life on-screen. Some want to take with them an idyllic moment from childhood, others a remembrance of a lost love, but a few are either unable to or refuse to come up with one, which challenges the staff. Twenty-one-year-old Yūsuke Iseya declares, “I have no intention of choosing. None,” while seventy-year-old Ichiro Watanabe (Taketoshi Naito) is having difficulty deciding on the exact moment, reevaluating and reflecting on the life he led. As the week continues, the guides look back on their lives as well, sharing intimate details, one of which leads to an emotional finale.

Kore-eda’s second narrative feature, After Life, is an eminently thoughtful film about two of his recurring themes: death and memory. Every Monday, the deceased arrive at a way station where they have three days to decide on a single memory they can bring with them into heaven. Once chosen, the memory is re-created on film, and the person goes on to the next step of his or her journey, to be replaced by a new batch of souls. The way station is staffed by guides, including Takashi Mochizuki (Arata), Shiori Satonaka (Erika Oda), and Satoru Kawashima (Susumu Terajima), whose job it is to interview the new arrivals and help them select a memory and then bring it to life on-screen. Some want to take with them an idyllic moment from childhood, others a remembrance of a lost love, but a few are either unable to or refuse to come up with one, which challenges the staff. Twenty-one-year-old Yūsuke Iseya declares, “I have no intention of choosing. None,” while seventy-year-old Ichiro Watanabe (Taketoshi Naito) is having difficulty deciding on the exact moment, reevaluating and reflecting on the life he led. As the week continues, the guides look back on their lives as well, sharing intimate details, one of which leads to an emotional finale.

Kore-eda, who previously examined memory loss in the documentary Without Memory and explored a family’s reaction to death in the brilliant Still Walking, interviewed some five hundred people about what memory they would take with them to heaven, and some of those nonprofessional actors are in the final cut of After Life, blurring the lines between fiction and reality. After Life is also very much about the art of filmmaking itself, as each memory is turned into a short movie created on a set and watched in a screening room. In fact, the film was inspired by Kore-eda’s memories of his grandfather’s battle with what would later be identified as Alzheimer’s disease; the director has also cited Ernst Lubitsch’s 1943 comedy, Heaven Can Wait, as an influence, and the Japanese title, Wandâfuru raifu, means “Wonderful Life,” evoking Frank Capra’s holiday classic. But Kore-eda never gets maudlin about life or death in the film, instead painting a memorable portrait of human existence and those simple moments that make it all worthwhile — and will have viewers contemplating which memory they would take with them.

NOBODY KNOWS (DAREMO SHIRANAI) (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2004)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

Tuesday, November 20, 6:00

Thursday, November 22, 4:00

www.kore-eda.com

Based on a true story that writer-director Kore-eda read about back in 1988, Nobody Knows is a heartwarming, heartbreaking film about four extraordinary half-siblings who must fend for themselves every time their mother takes off for extended periods of time. Japanese TV and pop star YOU makes her feature-film debut as Keiko, a young woman who has four kids by way of four different men. When she’s home, she shows affection for the children, but the problem is, she’s rarely home. Instead, twelve-year-old Akira (Yagira Yuya) must take care of the shy Kyoko (Kitaura Ayu), who handles the laundry; the troublemaker Shigeru (Kimura Hiei), who can’t follow the rules; and sweet baby Yuki (Shimizu Momoko), who likes chocolates and squeaky shoes. At first, it is charming and uplifting watching how Akira handles the complicated situation — the other kids are not allowed outside because the landlord will evict them if he finds out about them, and Akira even helps teach the family, who do not attend school — but as Keiko disappears for longer periods of time, the children’s lives grow more dire by the day as food and money start running out. Kore-eda, who also edited and produced this powerful picture, has created a moving, involving film that nearly plays like a documentary, avoiding melodramatic clichés and instead wrapping the audience up in the closeted life of four terrific kids whose tragic existence will ultimately break your heart.

Based on a true story that writer-director Kore-eda read about back in 1988, Nobody Knows is a heartwarming, heartbreaking film about four extraordinary half-siblings who must fend for themselves every time their mother takes off for extended periods of time. Japanese TV and pop star YOU makes her feature-film debut as Keiko, a young woman who has four kids by way of four different men. When she’s home, she shows affection for the children, but the problem is, she’s rarely home. Instead, twelve-year-old Akira (Yagira Yuya) must take care of the shy Kyoko (Kitaura Ayu), who handles the laundry; the troublemaker Shigeru (Kimura Hiei), who can’t follow the rules; and sweet baby Yuki (Shimizu Momoko), who likes chocolates and squeaky shoes. At first, it is charming and uplifting watching how Akira handles the complicated situation — the other kids are not allowed outside because the landlord will evict them if he finds out about them, and Akira even helps teach the family, who do not attend school — but as Keiko disappears for longer periods of time, the children’s lives grow more dire by the day as food and money start running out. Kore-eda, who also edited and produced this powerful picture, has created a moving, involving film that nearly plays like a documentary, avoiding melodramatic clichés and instead wrapping the audience up in the closeted life of four terrific kids whose tragic existence will ultimately break your heart.

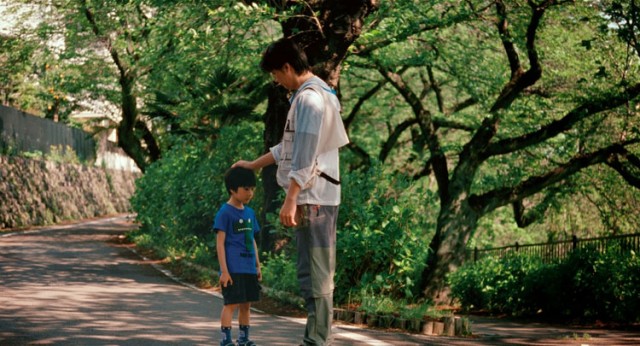

A father (Masaharu Fukuyama) must reevaluate his relationship with his son (Keita Ninomiya) in yet another Hirokazu Kore-eda masterpiece

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON (SOSHITE CHICHI NI NARU) (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2013)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

Tuesday, November 20, 8:45

Wednesday, November 21, 1:30

www.ifcfilms.com

International cinema’s modern master of the family drama turns out another stunner in the Cannes Jury Prize winner Like Father, Like Son. Ryota Nonomiya (Masaharu Fukuyama) thinks he has the perfect life: a beautiful wife, Midori (Machiko Ono), a successful job as an architect, and a splendid six-year-old son, Keita (Keita Ninomiya). But his well-structured world is turned upside down when the hospital where Keita was born suddenly tells them that Keita is not their biological son, that a mistake was made and a pair of babies were accidentally switched at birth. When Ryota and Midori meet Yudai (Lily Franky) and Yukari Saiki (Maki Yoko), whose infant was switched with theirs, Ryota is horrified to see that the Saikis are a lower-middle-class family who cannot give their children — they have three kids, including Ryusei (Shôgen Hwang), the Nonomiyas’ biological son — the same advantages that Ryota and Midori can. Meanwhile, the two mothers wonder why they were unable to realize that the sons they’ve been raising are not really their own. As the two families get to know each other and prepare to switch boys, Ryota struggles to reevaluate what kind of a father he is, as well as what kind of father he can be.

International cinema’s modern master of the family drama turns out another stunner in the Cannes Jury Prize winner Like Father, Like Son. Ryota Nonomiya (Masaharu Fukuyama) thinks he has the perfect life: a beautiful wife, Midori (Machiko Ono), a successful job as an architect, and a splendid six-year-old son, Keita (Keita Ninomiya). But his well-structured world is turned upside down when the hospital where Keita was born suddenly tells them that Keita is not their biological son, that a mistake was made and a pair of babies were accidentally switched at birth. When Ryota and Midori meet Yudai (Lily Franky) and Yukari Saiki (Maki Yoko), whose infant was switched with theirs, Ryota is horrified to see that the Saikis are a lower-middle-class family who cannot give their children — they have three kids, including Ryusei (Shôgen Hwang), the Nonomiyas’ biological son — the same advantages that Ryota and Midori can. Meanwhile, the two mothers wonder why they were unable to realize that the sons they’ve been raising are not really their own. As the two families get to know each other and prepare to switch boys, Ryota struggles to reevaluate what kind of a father he is, as well as what kind of father he can be.

Kore-eda wrote, directed, and edited Like Father, Like Son, imbuing the complex story with an Ozu-like austerity, examining a heartbreaking, seemingly no-win situation — one of every parent’s most-feared nightmares — with intelligence and grace. Musician and actor Fukuyama gives a powerfully understated performance as Ryota, a work-obsessed architect struggling to keep everything he has built from crumbling all around him. Novelist and actor Franky is excellent as his polar opposite, a man with a very different kind of verve for life. In Like Father, Like Son, Kore-eda, whose own father passed away ten years before and whose daughter was five years old when the film was made, once again explores the relationship between parents and children, this time focusing on the strong bonds created by both love and blood.

Real-life brothers Ohshirô Maeda and Koki Maeda star as close siblings in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s masterful I Wish

I WISH (KISEKI) (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2011)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

Wednesday, November 21, 4:00

Thursday, November 22, 1:30

www.magpictures.com/iwish

Kore-eda’s I Wish is an utterly delightful, absolutely charming tale of family and all of the hopes and dreams associated with it. Real-life brothers Koki Maeda and Ohshirô Maeda of the popular MaedaMaeda comedy duo star as siblings Koichi and Ryu, who have been separated as a result of their parents’ divorce. Twelve-year-old Koichi (Koki) lives with his mother (Nene Ohtsuka) and maternal grandparents (Kirin Kiki and Isao Hashizume) in Kagoshima in the shadow of an active volcano that continues to spit ash out all over the town, while the younger Ryu lives with his father (Joe Odagiri), a wannabe rock star, in Fukuoka. When Koichi hears that if a person makes a wish just as the two new high-speed bullet trains pass by each other for the first time the wish will come true, he decides he must do everything in his power to be there, along with Ryu, so they can wish for their family to get back together. Kore-eda once again displays his deft touch at handling complex relationships in I Wish, the Japanese title of which is Kiseki, or Miracle.

Kore-eda’s I Wish is an utterly delightful, absolutely charming tale of family and all of the hopes and dreams associated with it. Real-life brothers Koki Maeda and Ohshirô Maeda of the popular MaedaMaeda comedy duo star as siblings Koichi and Ryu, who have been separated as a result of their parents’ divorce. Twelve-year-old Koichi (Koki) lives with his mother (Nene Ohtsuka) and maternal grandparents (Kirin Kiki and Isao Hashizume) in Kagoshima in the shadow of an active volcano that continues to spit ash out all over the town, while the younger Ryu lives with his father (Joe Odagiri), a wannabe rock star, in Fukuoka. When Koichi hears that if a person makes a wish just as the two new high-speed bullet trains pass by each other for the first time the wish will come true, he decides he must do everything in his power to be there, along with Ryu, so they can wish for their family to get back together. Kore-eda once again displays his deft touch at handling complex relationships in I Wish, the Japanese title of which is Kiseki, or Miracle.

Originally intended to be a film about the new Kyushu Shinkansen bullet train, the narrative shifted once Kore-eda auditioned the Maeda brothers, deciding to make them the center of the story, and they shine as two very different siblings, one young and impulsive, the other older and far more serious. Everyone in the film, child and adult, wishes for something more out of life, whether realistic or not. Ryu’s friend Megumi (Kyara Uchida) wants to be an actress; Koichi’s friend Makoto (Seinosuke Nagayoshi) wants to be just like his hero, baseball star Ichiro Suzuki; and the brothers’ grandfather wants to make a subtly sweet, old-fashioned karukan cake that people will appreciate. Much of the dialogue is improvised, including by the children, lending a more realistic feel to the film, although it does get a bit too goofy in some of its later scenes. Written, directed, and edited by Kore-eda, I Wish is a loving, bittersweet celebration of the child in us all.

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Still Walking is a special film that honors such Japanese directors as Mikio Naruse, Yasujiro Ozu, and Shohei Imamura

STILL WALKING (ARUITEMO ARUITEMO) (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2008)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

Wednesday, November 21, 6:30

Thursday, November 22, 9:15

www.aruitemo.com

Flawlessly written, directed, and edited by Hirokazu Kore-eda, Still Walking follows a day in the life of the Yokoyama family, which gathers together once a year to remember Junpei, the eldest son who died tragically. The story is told through the eyes of the middle child, Ryota (Hiroshi Abe), a forty-year-old painting restorer who has recently married Yukari (Yui Natsukawa), a widow with a young son (Shohei Tanaka). Ryota dreads returning home because his father, Kyohei (Yoshio Harada), and mother, Toshiko (Kirin Kiki), are disappointed in the choices he’s made, both personally and professionally, and never let him escape from Junpei’s ever-widening shadow. Also at the reunion is Ryota’s chatty sister, Chinami (You), who, with her husband and children, is planning on moving in with her parents in order to take care of them in their old age (and save money as well). Over the course of twenty-four hours, the history of the dysfunctional family and the deep emotions hidden just below the surface slowly simmer but never boil, resulting in a gentle, bittersweet narrative that is often very funny and always subtly powerful.

Flawlessly written, directed, and edited by Hirokazu Kore-eda, Still Walking follows a day in the life of the Yokoyama family, which gathers together once a year to remember Junpei, the eldest son who died tragically. The story is told through the eyes of the middle child, Ryota (Hiroshi Abe), a forty-year-old painting restorer who has recently married Yukari (Yui Natsukawa), a widow with a young son (Shohei Tanaka). Ryota dreads returning home because his father, Kyohei (Yoshio Harada), and mother, Toshiko (Kirin Kiki), are disappointed in the choices he’s made, both personally and professionally, and never let him escape from Junpei’s ever-widening shadow. Also at the reunion is Ryota’s chatty sister, Chinami (You), who, with her husband and children, is planning on moving in with her parents in order to take care of them in their old age (and save money as well). Over the course of twenty-four hours, the history of the dysfunctional family and the deep emotions hidden just below the surface slowly simmer but never boil, resulting in a gentle, bittersweet narrative that is often very funny and always subtly powerful.

The film is beautifully shot by Yutaka Yamazaki, who keeps the camera static during long interior takes — it moves only once inside the house — using doorways, short halls, and windows to frame scenes with a slightly claustrophobic feel, evoking how trapped the characters are by the world the parents have created. The scenes in which Kyohei walks with his cane ever so slowly up and down the endless outside steps are simple but unforgettable. Influenced by such Japanese directors as Mikio Naruse, Yasujiro Ozu, and Shohei Imamura, Kore-eda was inspired to make the film shortly after the death of his parents; although it is fiction, roughly half of Toshiko’s dialogue is taken directly from his own mother. Still Walking is a special film, a visual and psychological marvel that should not be missed.