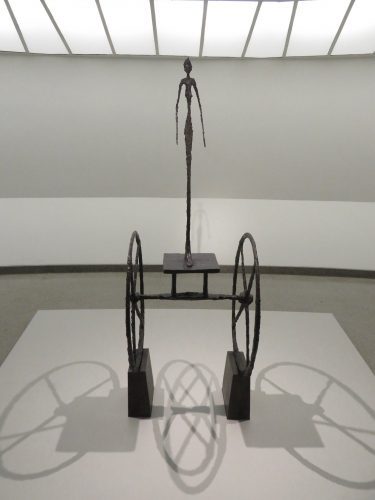

Albert Giacometti, “The Chariot,” bronze, 1950 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Ave. at 89th St.

Friday – Wednesday through September 12, $25 (pay-what-you-wish Saturday 5:00-7:45)

212-423-3587

www.guggenheim.org

In his catalog essay “The Quest for the Absolute” for Alberto Giacometti’s 1948 solo show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York, Jean-Paul Sartre began, “I know no one else so sensitive as he is to the magic of faces and gestures. He views them with a passionate desire, as though he were from some other realm. But at times, tiring of the struggle, he has sought to mineralize his fellow human beings: he saw crowds advancing blindly toward him, rolling down the avenues like rocks in an avalanche. So each of his obsessions remained a piece of work, an experiment, a way of experiencing space.” Humanness and space are key to the Guggenheim’s outstanding current retrospective, simply titled “Giacometti,” where large crowds are expected in its final days; the exhibition ends September 12. Although Giacometti, who was born in Switzerland in 1901, spent most of his working life in Paris, and died in 1966, came to New York only once, for a MoMA show in 1965, he has had a long and important relationship with the city.

Two versions of “Spoon Woman” (1927) are side by side, bronze in black, plaster in white (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Following gallery shows at Pierre Matisse and Julien Levy, Giacometti was given a major exhibition at the Guggenheim’s temporary space in 1955, and nineteen years later the institution mounted a posthumous retrospective in its Frank Lloyd Wright building. The new show is beautifully curated by the museum’s Megan Fontanella and Fondation Giacometti director Catherine Grenier and smartly installed by Derek DeLuco, with the artist’s large and small bronze and plaster sculptures, paintings, drawings, notebooks, and more unfolding chronologically up the Guggenheim’s spiral pathway, revealing a fascinating array of humanity and artistic styles (Surrealism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Egyptian and African), with plenty of room for both the visitor and the work to breathe.

A group of small busts line one bay at the Guggenheim (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The High Gallery provides a kind of amuse-bouche, a tantalizing look at Giacometti’s designs for an unrealized 1958 project at the Chase Manhattan Bank plaza downtown. Back on the ramp, bays feature black bronze and white plaster versions of the abstract “Spoon Woman,” an early gestation of the more familiar sculptures to come. “Suspended Ball” is a piece of Surrealist illusion. “Woman with Her Throat Cut” and “Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object)” offer compelling narratives. “Very Small Figurine” is just that, not even two inches tall, in contrast to, for example, “Man Pointing,” which reaches nearly six feet. (If it looks like the man’s left arm is cradling a missing figure, that’s because it is; Giacometti destroyed it, preferring to have the man be more lonely, particularly in the aftermath of WWII.) “City Square” brings together a handful of eight-inch figures that form a little community, while “Four Women on a Base” comprises a quartet of narrow figures who are so thin they nearly disappear. “In the street people astound and interest me more than any sculpture and painting,” Giacometti said. “They form and re-form living compositions in unbelievable complexity. It’s the totality of this life that I want to reproduce in everything I do.”

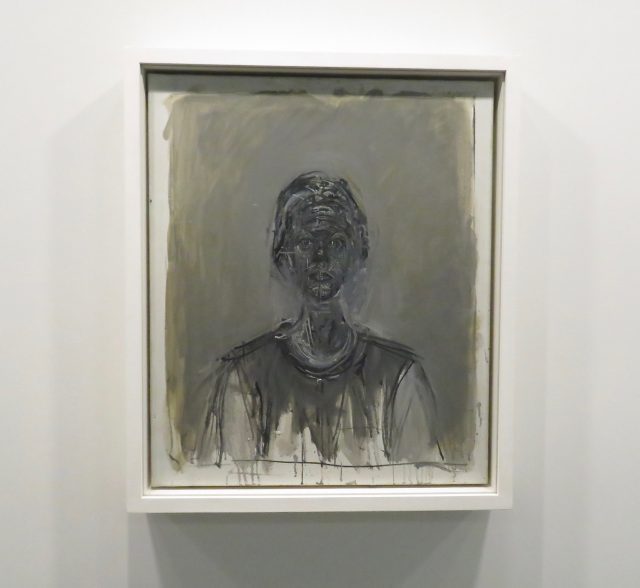

Guggenheim retrospective begins with Giacometti’s 1962 oil painting of his wife, titled “Black Annette” (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

In “The Nose,” the lengthy proboscis of a figure in an open box pokes outside the plane. “Figurine Between Two Houses” resembles a man in a console television set. A woman stands tall on a small platform with two large wheels in “The Chariot,” which casts stunning shadows below it. Oil paintings such as “Standing Nude,” “Black Annette,” “Diego Standing in the Living Room in Stampa” (Diego was his brother and longtime model as well as a sculptor and designer), and “Jean Genet” prove Giacometti’s intense skill with canvas. The show is so well laid out that a visitor eagerly looks forward to what awaits in the next bay rather than tiring of so many elongated figures; they can seem like a sequence of musical notes, rising and falling as one proceeds through the show. “In space, there is too much,” Sartre quotes Giacometti, but that is not true of this thrilling, must-see retrospective.