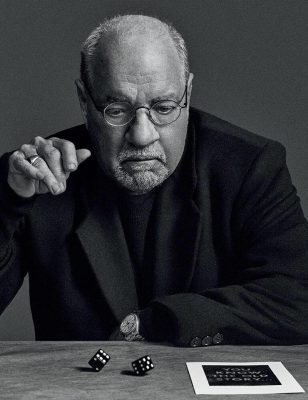

Paul Schrader will be at the Quad for series of film screenings he has selected (photo courtesy Paul Schrader)

In conjunction with the theatrical release of his new thriller, First Reformed, which opens May 18, and the publication of an updated edition of his 1972 book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, Michigan-born auteur Paul Schrader — who, curiously, has never been nominated for an Oscar despite writing and/or directing such films as Taxi Driver, Blue Collar, Raging Bull, and Affliction — will be at the Quad for several screenings in the upcoming series “Origin Stories: Paul Schrader’s Footnotes to First Reformed.” Running May 11-15, the series comprises fourteen films selected by Schrader that impacted his life and career, with Schrader present for Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Ordet on May 11 at 6:45, Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest on May 11 at 9:25, Carlos Reygadas’s Silent Light on May 12 at 4:15, and Paweł Pawlikowski’s Ida on May 12 at 7:00. The impressive lineup also includes Yasujirō Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert, Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T, Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy, and Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light, among other international gems.

Ida (Agata Trzebuchowska) learns surprising things about her family from her aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza) in Ida

IDA (Paweł Pawlikowski, 2013)

Quad Cinema

34 West 13th St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Saturday, May 12, 7:00 (with Schrader), and Monday, May 14, 4:30

Series runs May 11-15

212-255-2243

quadcinema.com

www.musicboxfilms.com

Paweł Pawlikowski’s Ida is one of the most gorgeously photographed, beautifully told films of the young century. The international festival favorite and Foreign Language Oscar winner is set in Poland in 1962, as eighteen-year-old novitiate Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is preparing to become a nun and dedicate her life to Christ. But the Mother Superior (Halina Skoczyńska) tells Anna, an orphan who was raised in the convent, that she actually has a living relative, an aunt whom she should visit before taking her vows. So Anna sets off by herself to see her aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a drinking, smoking, sexually promiscuous, and deeply bitter woman who explains to Ida that her real name is Ida Lebenstein and that she is in fact Jewish — and then reveals what happened to her family. Soon Ida, Wanda, and hitchhiking jazz saxophonist Dawid Ogrodnik are on their way to discovering some unsettling truths about the past.

Paweł Pawlikowski’s Ida is one of the most gorgeously photographed, beautifully told films of the young century. The international festival favorite and Foreign Language Oscar winner is set in Poland in 1962, as eighteen-year-old novitiate Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is preparing to become a nun and dedicate her life to Christ. But the Mother Superior (Halina Skoczyńska) tells Anna, an orphan who was raised in the convent, that she actually has a living relative, an aunt whom she should visit before taking her vows. So Anna sets off by herself to see her aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a drinking, smoking, sexually promiscuous, and deeply bitter woman who explains to Ida that her real name is Ida Lebenstein and that she is in fact Jewish — and then reveals what happened to her family. Soon Ida, Wanda, and hitchhiking jazz saxophonist Dawid Ogrodnik are on their way to discovering some unsettling truths about the past.

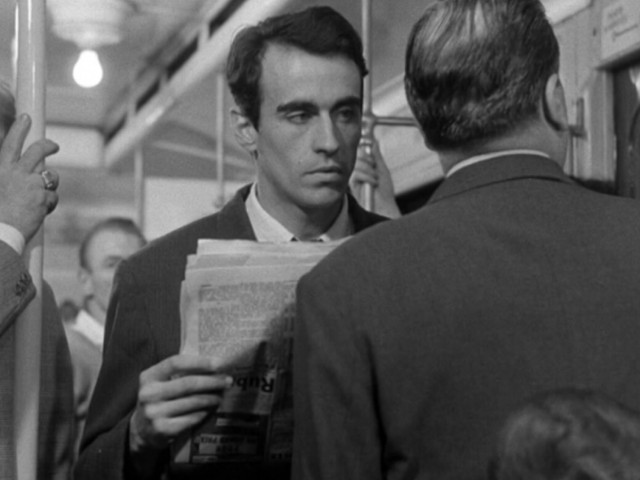

Lis (Dawid Ogrodnik) and Ida (Agata Trzebuchowska) discuss life and loss in beautifully photographed Ida

Polish-born writer-director Pawlikowski (Last Resort, My Summer of Love), who lived and worked in the UK for more than thirty years before moving back to his native country to make Ida, composes each shot of the black-and-white film as if it’s a classic European painting, with Oscar-nominated cinematographers Łukasz Żal and Ryszard Lenczewski’s camera remaining static for nearly every scene. Pawlikowski often frames shots keeping the characters off to the side or, most dramatically, at the bottom of the frame, like they are barely there as they try to find their way in life. (At these moments, the subtitles jump to the top of the screen so as not to block the characters’ expressions.) Kulesza (Róża) is exceptional as the emotionally unpredictable Wanda, who has buried herself so deep in secrets that she might not be able to dig herself out. And in her first film, Trzebuchowska — who was discovered in a Warsaw café by Polish director Małgorzata Szumowska — is absolutely mesmerizing, her headpiece hiding her hair and ears, leaving the audience to focus only on her stunning eyes and round face, filled with a calm mystery that shifts ever so subtly as she learns more and more about her family, and herself. It’s like she’s stepped right out of a Vermeer painting and into a world she never knew existed. The screenplay, written by Pawlikowski and theater and television writer Rebecca Lenkiewicz, keeps the dialogue to a minimum, allowing the stark visuals and superb acting to heighten the intensity. Ida is an exquisite film whose dazzling grace cannot be overstated.

SILENT LIGHT (STELLET LICHT) (Carlos Reygadas, 2007)

Saturday, May 12, 4:15 (with Schrader, and Monday, May 14, 8:30

quadcinema.com

Carlos Reygadas’s Silent Light is a gentle, deeply felt, gorgeously shot work of intense calm and beauty. The film opens with a stunning sunrise and ends with a glorious sunset; in between is scene after scene of sublime beauty and simplicity, as Reygadas uses natural sound and light, a cast of mostly nonprofessional actors, and no incidental music to tell his story, allowing it to proceed naturally. In a Mennonite farming community in northern Mexico where Plautdietsch is the primary language, Johan (Cornelio Wall Fehr) is torn between his wife, Esther (Miriam Toews), and his lover, Marianne (Maria Pankratz). While he loves Esther, he finds a physical and spiritual bond with Marianne that he does not feel with his spouse and their large extended family. Although it pains Johan deeply to betray Esther, he is unable to decide between the two women, even after tragedy strikes. Every single shot of the spare, unusual film, which tied for the Jury Prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival (with Vincent Paronnaud and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis), is meticulously composed by Reygadas (Japon, Battle in Heaven) and cinematographer Alexis Zabe, as if a painting. Many of the scenes consist of long takes with little or no camera movement and sparse dialogue, evoking the work of Japanese minimalist master Yasujirō Ozu. The lack of music evokes the silence of the title, but the quiet, filled with space and meaning, is never empty. And the three leads — Fehr, who lives in Mexico; Toews, who is from Canada; and Pankratz, who was born in Kazakhstan and lives in Germany — are uniformly excellent in their very first film roles. Silent Light, which was shown at the 2007 New York Film Festival, is a mesmerizing, memorable, and very different kind of cinematic experience.

Carlos Reygadas’s Silent Light is a gentle, deeply felt, gorgeously shot work of intense calm and beauty. The film opens with a stunning sunrise and ends with a glorious sunset; in between is scene after scene of sublime beauty and simplicity, as Reygadas uses natural sound and light, a cast of mostly nonprofessional actors, and no incidental music to tell his story, allowing it to proceed naturally. In a Mennonite farming community in northern Mexico where Plautdietsch is the primary language, Johan (Cornelio Wall Fehr) is torn between his wife, Esther (Miriam Toews), and his lover, Marianne (Maria Pankratz). While he loves Esther, he finds a physical and spiritual bond with Marianne that he does not feel with his spouse and their large extended family. Although it pains Johan deeply to betray Esther, he is unable to decide between the two women, even after tragedy strikes. Every single shot of the spare, unusual film, which tied for the Jury Prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival (with Vincent Paronnaud and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis), is meticulously composed by Reygadas (Japon, Battle in Heaven) and cinematographer Alexis Zabe, as if a painting. Many of the scenes consist of long takes with little or no camera movement and sparse dialogue, evoking the work of Japanese minimalist master Yasujirō Ozu. The lack of music evokes the silence of the title, but the quiet, filled with space and meaning, is never empty. And the three leads — Fehr, who lives in Mexico; Toews, who is from Canada; and Pankratz, who was born in Kazakhstan and lives in Germany — are uniformly excellent in their very first film roles. Silent Light, which was shown at the 2007 New York Film Festival, is a mesmerizing, memorable, and very different kind of cinematic experience.

Michel (Martin LaSalle) eyes a potential target in Robert Bresson’s highly influential masterpiece Pickpocket

PICKPOCKET (Robert Bresson, 1959)

Saturday, May 12, 1:00

718-636-4100

quadcinema.com

Robert Bresson’s 1959 Pickpocket is a stylistic marvel, a brilliant examination of a deeply troubled man and his dark obsessions. Evoking Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Martin LaSalle made his cinematic debut as Michel, a ne’er-do-well Parisian who lives in a decrepit apartment, refuses to visit his ailing mother (Dolly Scal), and decides to become a pickpocket. But it’s not necessarily the money he’s after; he hides the cash and watches that he steals in his room, which he is unable to lock from the outside. Instead, his petty thievery seems to give him some kind of psychosexual thrill, although his pleasure can seldom be seen in his staring, beady eyes. As the film opens, Michel is at the racetrack, dipping his fingers into a woman’s purse in an erotically charged moment that is captivating, instantly turning the viewer into voyeur. Of course, film audiences by nature are a kind of peeping Tom, but Bresson makes them complicit in Michel’s actions; although there is virtually nothing to like about the character, who is distant and aloof when not being outright nasty, even to his only friends, Jacques (Pierre Leymarie) and Jeanne (Marika Green), the audience can’t help but breathlessly root for him to succeed as he dangerously dips his hands into men’s pockets on the street and in the Metro. Soon he is being watched by a police inspector (Jean Pélégri), to whom he daringly gives a book about George Barrington, the famed “Prince of Pickpockets,” as well as a stranger (Kassagi) who wants him to join a small cadre of thieves, leading to a gorgeously choreographed scene of the men working in tandem as they pick a bunch of pockets. Through it all, however, Michel remains nonplussed, living a strange, private life, uncomfortable in his own skin. “You’re not in this world,” Jeanne tells him at one point.

Robert Bresson’s 1959 Pickpocket is a stylistic marvel, a brilliant examination of a deeply troubled man and his dark obsessions. Evoking Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Martin LaSalle made his cinematic debut as Michel, a ne’er-do-well Parisian who lives in a decrepit apartment, refuses to visit his ailing mother (Dolly Scal), and decides to become a pickpocket. But it’s not necessarily the money he’s after; he hides the cash and watches that he steals in his room, which he is unable to lock from the outside. Instead, his petty thievery seems to give him some kind of psychosexual thrill, although his pleasure can seldom be seen in his staring, beady eyes. As the film opens, Michel is at the racetrack, dipping his fingers into a woman’s purse in an erotically charged moment that is captivating, instantly turning the viewer into voyeur. Of course, film audiences by nature are a kind of peeping Tom, but Bresson makes them complicit in Michel’s actions; although there is virtually nothing to like about the character, who is distant and aloof when not being outright nasty, even to his only friends, Jacques (Pierre Leymarie) and Jeanne (Marika Green), the audience can’t help but breathlessly root for him to succeed as he dangerously dips his hands into men’s pockets on the street and in the Metro. Soon he is being watched by a police inspector (Jean Pélégri), to whom he daringly gives a book about George Barrington, the famed “Prince of Pickpockets,” as well as a stranger (Kassagi) who wants him to join a small cadre of thieves, leading to a gorgeously choreographed scene of the men working in tandem as they pick a bunch of pockets. Through it all, however, Michel remains nonplussed, living a strange, private life, uncomfortable in his own skin. “You’re not in this world,” Jeanne tells him at one point.

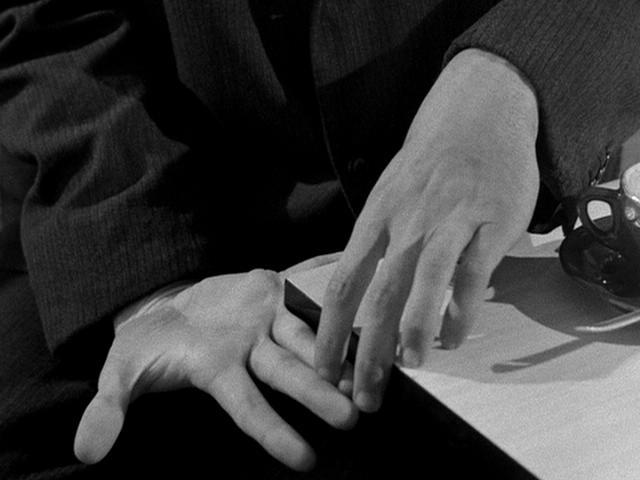

Michel (Martin LaSalle) can’t keep his hands to himself in Bresson classic chosen by Paul Schrader for Quad series

Bresson (Au hasard Balthazar, Diary of a Country Priest) fills Pickpocket with visual clues and repeated symbols that add deep layers to the narrative, particularly an endless array of shots of hands and a parade of doors, many of which are left ajar and/or unlocked in the first half of the film but are increasingly closed as the end approaches. Shot in black-and-white by Léonce-Henri Burel — Bresson wouldn’t make his first color film until 1969’s Un femme douce — Pickpocket also has elements of film noir that combine with a visual intimacy to create a moody, claustrophobic feeling that hovers over and around Michel and the story. It’s a mesmerizing performance in a mesmerizing film, one of the finest of Bresson’s remarkable, and remarkably influential, career.