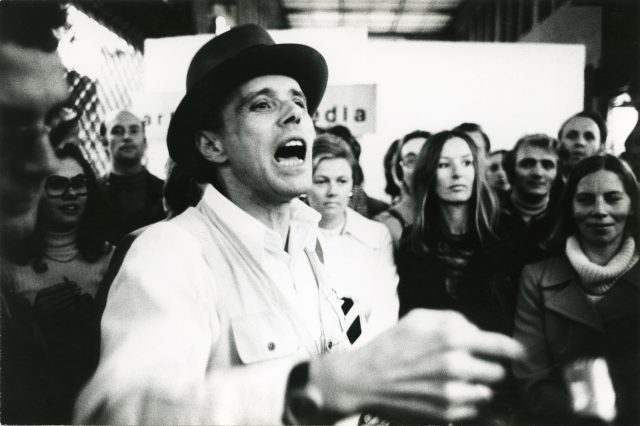

Joseph Beuys declares that everything is art and everyone is an artist in new documentary (copyright zeroonefilm/bpk _ErnstvonSiemensKunststiftung_StiftungMuseumSchlossMoyland_Foto: UteKlophaus)

BEUYS (Andres Veiel, 2017)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Opens Wednesday, January 17

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

About ten years ago, I was visiting Chelsea galleries on a sunny afternoon when a car pulled up on the corner of Eleventh Ave. and Twenty-second St. A father and a young boy of about five or six got out, and the man led the child to one of the stone sculptures that make up Joseph Beuys’s “7000 Oaks.” The boy relieved himself on the stone; the pair then returned to the car and the family drove off. I always thought that the German avant-garde artist would have gotten a kick out of that scene; after watching Andres Veiel’s new documentary, Beuys, I’m sure of it. If you’re going to make a documentary about Beuys (pronounced boys), one of the most influential artists of the postwar generation, it had better not be a straightforward, talking-heads film but something that pushes the boundaries and challenges the viewer, much like his art. Award-winning director Veiel (Balagan, Black Box Germany) does just that with the film, which concentrates primarily on rarely shown and never-before-seen archival footage of Beuys, including radio and television interviews, art openings, panel discussions, live performances, photographs, and home movies, mostly in black-and-white. Veiel conducted approximately twenty new interviews and met with more than five dozen people who knew Beuys, but he only uses spare clips from art historian Rhea Thönges-Stringaris, publisher Klaus Staeck, collector Franz Joseph van der Grinten, and critic, curator, and writer Caroline Tisdall, who wrote seven books about Beuys and worked with him on several major exhibitions and lecture tours. “The anonymous viewer is back there, yeah?” Beuys says early on, looking straight into the camera, and it’s a critical moment, as the documentary emphasizes how important it was to him that his work be seen. “I want to inform people about the true culprits in our system. I want to inform and educate people,” he says. Beuys, who also taught at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, is eminently quotable, his speech filled with manifesto-like declarations. “Forget the conventional idea of art. Anyone can be an artist. Anything can be art, especially anything that conserves energy,” he explains. “I’m not an artist at all. Except if we say that everyone is an artist,” he opines. “The concept of what art is has expanded to such a degree that, for me, there’s nothing left of it,” he offers.

About ten years ago, I was visiting Chelsea galleries on a sunny afternoon when a car pulled up on the corner of Eleventh Ave. and Twenty-second St. A father and a young boy of about five or six got out, and the man led the child to one of the stone sculptures that make up Joseph Beuys’s “7000 Oaks.” The boy relieved himself on the stone; the pair then returned to the car and the family drove off. I always thought that the German avant-garde artist would have gotten a kick out of that scene; after watching Andres Veiel’s new documentary, Beuys, I’m sure of it. If you’re going to make a documentary about Beuys (pronounced boys), one of the most influential artists of the postwar generation, it had better not be a straightforward, talking-heads film but something that pushes the boundaries and challenges the viewer, much like his art. Award-winning director Veiel (Balagan, Black Box Germany) does just that with the film, which concentrates primarily on rarely shown and never-before-seen archival footage of Beuys, including radio and television interviews, art openings, panel discussions, live performances, photographs, and home movies, mostly in black-and-white. Veiel conducted approximately twenty new interviews and met with more than five dozen people who knew Beuys, but he only uses spare clips from art historian Rhea Thönges-Stringaris, publisher Klaus Staeck, collector Franz Joseph van der Grinten, and critic, curator, and writer Caroline Tisdall, who wrote seven books about Beuys and worked with him on several major exhibitions and lecture tours. “The anonymous viewer is back there, yeah?” Beuys says early on, looking straight into the camera, and it’s a critical moment, as the documentary emphasizes how important it was to him that his work be seen. “I want to inform people about the true culprits in our system. I want to inform and educate people,” he says. Beuys, who also taught at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, is eminently quotable, his speech filled with manifesto-like declarations. “Forget the conventional idea of art. Anyone can be an artist. Anything can be art, especially anything that conserves energy,” he explains. “I’m not an artist at all. Except if we say that everyone is an artist,” he opines. “The concept of what art is has expanded to such a degree that, for me, there’s nothing left of it,” he offers.

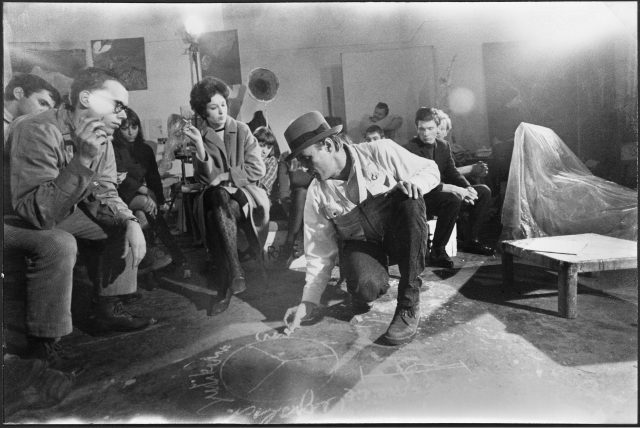

Wearing his trademark outfit, Joseph Beuys shares his thoughts about art and life (copyright zeroonefilm_bpk _ Stiftung_MuseumSchloss_Moyland_UteKlophaus)

Veiel, cinematographer Jörg Jeshel, and editors Olaf Voigtländer and Stephan Krumbiegel begin many scenes by scanning a contact sheet of photos of Beuys and zeroing in on one, which suddenly comes to life. Among Beuys’s projects they focus on are 1969’s “The Pack” (das Rudel), sleds tied to the back of a VW bus; the 1974-75 installation “Show Your Wound,” which might have been inspired by the injuries he suffered as a pilot in WWII; the 1965 performance piece “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare”; “Boxing Match: Joseph Beuys & Abraham David Christian”; “Honey Pump in the Workplace,” an example of what Beuys called “social sculpture”; and the expansive “7000 Oaks,” in which he paired stone sculptures with tree plantings. Usually smoking a cigarette, baring his big, white teeth, and wearing his vest and trademark hat — perhaps to cover up war injuries — Beuys is always aware he is being watched, on exhibit himself, and it’s something he toys with, tongue often in cheek as he expounds on concepts about life and art and plays around with interlocutors. The film touches on his childhood, his war experience, his association with the Green Party, and his descent into a deep, dark depression, but it evades various controversies, from possible Nazi ties to shamanism to his oft-told tale of a plane crash in which he was supposedly saved by Tartars. Veiel also doesn’t delve into Beuys’s personal relationships or the illness that led to his death in 1986 at the age of sixty-four. Instead, he gives us a Beuys who is ever-present, an iconoclastic, often inscrutable, and wildly intelligent artist and innovative provocateur who constructed his own mythology that continues to tantalize us today — even when his work is used as a public toilet. Beuys is making its U.S. theatrical premiere January 17 at Film Forum; Veiel will participate in a Q&A with MoMA PS1 director Klaus Biesenbach following the 7:00 show on January 19.