Chantal Akerman’s HOTEL MONTEREY was filmed in an Upper West Side transient hotel

HOTEL MONTEREY (Chantal Akerman, 1972) and LA CHAMBRE (Chantal Akerman, 1972)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

30 Lafayette Ave. between Ashland Pl. & St. Felix St.

Friday, April 8, 2:30 & 7:30

Series continues through May 1

718-636-4100

www.bam.org

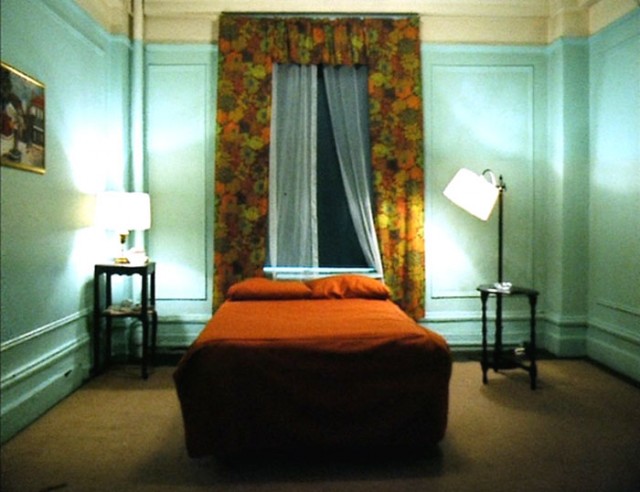

BAMcinématek continues its month-long tribute to the late Chantal Akerman, which began April 1 with a two-week run of the Belgian auteur’s latest, and last, film, No Home Movie, with a double feature of two extraordinary experimental works she made while living in New York City in the early 1970s. In 1972, following 1968’s Saute ma ville and 1971’s L’enfant aimé ou Je joue à être une femme mariée, Akerman and cinematographer Babette Mangolte took a camera to the Hotel Monterey, an Upper West Side welfare hotel, and set it up in the lobby, elevator, and various floors as it made its way upstairs and ultimately to an open window, where it ventures outside into the gray dimness of the city. The camera very rarely moves before then, instead capturing curious residents as they hang out in the lobby, look into the lens, or choose not to get into the dark elevator with the unexpected object; each shot lasts approximately one minute, and the entire film is silent. In hallways, the static shots sometimes look like photographs or paintings, the dreary, fading colors of the walls and floors adding a haunting, mysterious quality that is at times eerily reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, which came out eight years later, while also evoking Michael Snow’s Wavelength. Occasionally, the camera enters a room: in one, a pregnant woman looks off in a Vermeer-like pose; in another, a well-dressed gentleman sits in a chair, looking directly into the lens; and in a third, a woman sits in a chair by a window, as if wondering what awaits her. A shot of an empty room with a striking red bed in the center can’t help but lead viewers into creating their own stories about what might have gone on there. Artfully edited by Geneviève Luciani, Hotel Monterey is a mesmerizing, and challenging, sixty-five-minute architectural journey into the physical and psychological properties of what film can show and how it is perceived.

BAMcinématek continues its month-long tribute to the late Chantal Akerman, which began April 1 with a two-week run of the Belgian auteur’s latest, and last, film, No Home Movie, with a double feature of two extraordinary experimental works she made while living in New York City in the early 1970s. In 1972, following 1968’s Saute ma ville and 1971’s L’enfant aimé ou Je joue à être une femme mariée, Akerman and cinematographer Babette Mangolte took a camera to the Hotel Monterey, an Upper West Side welfare hotel, and set it up in the lobby, elevator, and various floors as it made its way upstairs and ultimately to an open window, where it ventures outside into the gray dimness of the city. The camera very rarely moves before then, instead capturing curious residents as they hang out in the lobby, look into the lens, or choose not to get into the dark elevator with the unexpected object; each shot lasts approximately one minute, and the entire film is silent. In hallways, the static shots sometimes look like photographs or paintings, the dreary, fading colors of the walls and floors adding a haunting, mysterious quality that is at times eerily reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, which came out eight years later, while also evoking Michael Snow’s Wavelength. Occasionally, the camera enters a room: in one, a pregnant woman looks off in a Vermeer-like pose; in another, a well-dressed gentleman sits in a chair, looking directly into the lens; and in a third, a woman sits in a chair by a window, as if wondering what awaits her. A shot of an empty room with a striking red bed in the center can’t help but lead viewers into creating their own stories about what might have gone on there. Artfully edited by Geneviève Luciani, Hotel Monterey is a mesmerizing, and challenging, sixty-five-minute architectural journey into the physical and psychological properties of what film can show and how it is perceived.

LA CHAMBRE repeatedly scans a downtown tenement apartment, where the director alluringly waits in bed

The day after shooting Hotel Monterey, Akerman and Mangolte went downtown to SoHo, where they made La Chambre, an eleven-minute silent film influenced by Snow’s <----> (“Back and Forth”). In a cramped room in a tenement house where Akerman occasionally stayed, a camera slowly pans around the space, sometimes stuttering to remind the viewer that there is someone holding it. The camera treats every object the same, revolving past a table, a sink, a stovetop with a kettle on it, and Akerman in a white nightgown in bed. As it returns to familiar spots, you look deeper, perhaps to see if you missed anything the previous time, or to check if something changed, a natural inclination while watching a movie. However, the only element that changes is Akerman herself; each time the camera pans by her, she is in a slightly different position, fully aware she is being watched — but taking the power back as she stares directly into the camera, playing off her sexuality. She even picks up an apple and lasciviously takes a bite out of it, referencing Eve in the Garden of Eden. And then the camera suddenly goes from rotating counterclockwise to clockwise, completely shifting the visual narrative while obliterating all expectations, Akerman boldly telling everyone who is in control. It’s a thrilling eleven minutes that makes you rethink the way you experience cinema, especially in this age of social media and constant surveillance; in the early 1970s, people did not have the same opportunities to post aspects of their everyday life for all to see, and they were not used to being on camera everywhere they went, including lobbies and elevators.

Both La Chambre and Hotel Monterey, along with Saute ma ville, which is also set in small rooms, reveal Akerman’s fondness for shooting in tight, often confining spaces. For the Brussels-born director, these tableaux evoked her mother’s imprisonment in Auschwitz as well as the trapped role of women in society. “We can read the Akerman-room as a sort of artist’s installation, a reduced stage on which the filmmaker reenacts her agency as artist,” Ivone Margulies explains in “La Chambre Akerman: The Captive as Creator,” a paper delivered at the December 2005 symposium “Images between Images” at Princeton. “Despite the affinity of this room with other video and performance images, ‘la chambre Akerman’ can be found only in her films. For this room gains its performative raison d’être from its relations to other spaces. The primary impetus for the room is its erection of a separate, rigorously demarcated space for the self. . . . The Akerman-chamber works as a display case for the conflict between artistic autonomy and the temptations of another less productive, obsessive kind of autonomy.” Throughout her career, Akerman, who was also a writer and installation artist, was nothing if not autonomous and obsessive; she actually made Hotel Monterey and La Chambre with money she had skimmed from her job at a gay porn theater in New York. All of the elements would later come together in her boundary-shattering feminist classic, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Akerman died last October, reportedly by suicide, shortly after the death of her mother. “Chantal Akerman: Images between the Images” continues through May 1 with such other films by Akerman as Tomorrow We Move, The Meetings of Anna, From the Other Side, News from Home, and La Captive. In addition, Jeanne Dielman is at Film Forum through April 7 and Anthology Film Archives will host “Chantal Akerman x 2,” showing No Home Movie and Là-Bas April 15-21.