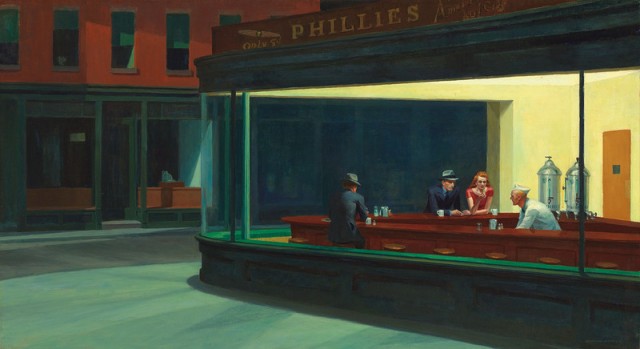

Edward Hopper, “Nighthawks,” oil on canvas, 1942 (Friends of American Art Collection, Art Institute of Chicago)

Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.

Wednesday – Sunday through October 6, $16-$20 (pay-what-you-wish Fridays, 6:00 – 9:00)

212-570-3600

www.whitney.org

There are only five days left to see the most exciting room in any New York City museum right now, the centerpiece of the Whitney’s “Hopper Drawing” exhibit, which continues through Sunday. Although the primary focus of the show is the New York realist’s drawings and preparatory sketches, the well-curated display also includes two of Edward Hopper’s greatest paintings, installed across from each other in a spacious gallery. On one wall hangs Hopper’s most famous work, 1942’s “Nighthawks,” a bravura noir oil of light, shadow, and color in which a lone man and a couple sit at a diner counter being served by a male worker in white. Every detail in the masterful composition, inspired by a Greenwich Village street and, perhaps, the Flatiron Building, is a wonder to observe. Seeing it in this context, the viewer is able to remove all of the meta surrounding the work, the endless parodies, homages, rip-offs, and tributes that keep coming and instead just appreciate the dazzling glory of the original. It’s a genuine treat to see “Nighthawks” in New York, as it’s on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago, where it’s been ever since Daniel Catton Rich bought it from Hopper for three thousand dollars shortly after it was completed. On May 13, 1942, Hopper sent a letter to Rich, explaining, “It is, I believe, one of the very best things I have painted. I seem to have come nearer to saying what I want to say in my work, this past winter, than I ever have before.”

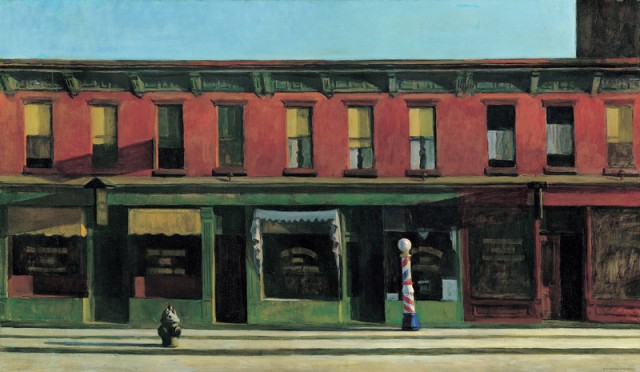

Edward Hopper, “Early Sunday Morning,” oil on canvas, 1930 (© Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art)

On the other side of the room, in the corner on a platform, resides one of the other very best things Hopper painted, the Whitney’s own “Early Sunday Morning.” Placed on Hopper’s easel in the corner, echoing the architectural layout in “Nighthawks,” the 1930 oil painting depicts a depression-era Seventh Ave. devoid of people as dawn breaks. Hopper re-creates a horizontal two-story building, the ground floor consisting of closed businesses with blurred names, the second floor comprising apartments with shades drawn at different levels, implying some kind of life going on inside. A fire hydrant and a barbershop pole, along with an unseen element, cast shadows, while an ominous dark rectangle in the upper right corner, contrasting with the blue of the sky, portends to the coming of monstrous skyscrapers that would signal the end of small-town living. The canvas’s deceptive simplicity is both devastating and mesmerizing, worthy of extended viewing that is sure to produce powerful emotional reactions. “Early Sunday Morning” marvelously captures an America teetering between the Great Depression and FDR’s New Deal, a moment in time when the future was as uncertain as it’s ever been. Perhaps some of those people missing in “Early Sunday Morning” found themselves still lost a dozen years later, sitting silently in a dark corner diner, wondering where things might have gone wrong. Related drawings, audio, video, and wall text further explore the creative process Hooper employed in both works, including trying to find the precise geographic locations that influenced these majestic paintings, which, seen together, shed even more light on their brilliance.