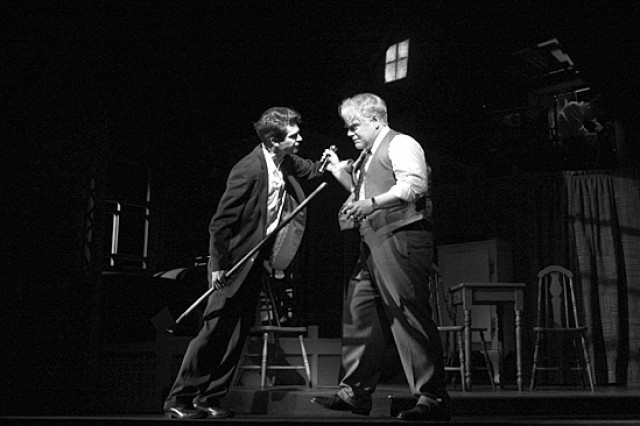

Philip Seymour Hoffman and Linda Emond hope for better days in DEATH OF A SALESMAN (photo by Brigitte Lacombe)

Ethel Barrymore Theatre

243 West 47th St.

February 13 – June 2

deathofasalesmanbroadway.com

Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman stakes its claim once again as the Great American Play in Mike Nichols’s poignant new version, running at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre through June 2. Winner of the 1949 Pulitzer Prize, Death of a Salesman is about nothing less than the death of the American dream. Willy Loman (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is a traveling salesman who has just returned to his New York City home after an aborted attempt at a sales trip to New England. A sixty-three-year-old man who has worked for the same company for thirty-six years, Loman has been beaten down, left out of the booming post-WWII economy and lagging behind changing times. He is consoled by his gentle, stalwart wife, Linda (Linda Emond), who reminds him that both of his grown sons are back in their room upstairs, sleeping soundly. The older Biff (Andrew Garfield) has yet to find himself, having recently spent time on a farm in Texas despite grand hopes, while the younger Hap (Finn Wittrock) is a ladies’ man with big dreams of going into business with his brother. Over the course of a single day, the Lomans are forced to face some hard, cold truths about themselves and their uncertain future. Hoffman is magnificent as Loman, his barren eyes haunted by his lack of success, his body hunched over, dragging around a briefcase filled with meaningless items he has been hawking for decades — items that are never specified, because it doesn’t matter; they could be anything. All he wants is to be able to complete the payments on an appliance before it breaks, to have at least one of his sons make something of his life, to own something of value. Willy is overwhelmed by flashbacks and memories that remind him of what could have been, drifting in and out of conversations with his brother Ben (John Glover), an adventurer who struck it rich in Alaska, and with a younger Biff as he prepares for the football game that will likely earn him a college scholarship.

Hoffman — who played a theater director staging a unique version of Death of a Salesman in Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York — is not made up to look much older than he actually is, yet he embodies the wear and tear that has ravaged Loman’s body, mind, and spirit. At forty-four, Hoffman is not the youngest actor to take on the iconic role; Loman originator Lee J. Cobb was a mere thirty-seven, while Dustin Hoffman was forty-six, George C. Scott forty-seven, Brian Dennehy sixty, and Fredric March fifty-three in the 1951 film. But Hoffman plays old marvelously, his Loman an everyman for whom age is not the central problem. Nichols has brought back Death of a Salesman at a critical juncture in American history, when the separation between the haves and the have-nots keeps widening amid mortgage failures and bank bailouts, ripping an ever-widening hole in the fabric of the nation. But Hoffman’s Loman (low man) is no mere victim seeking sympathy; he has been complicit in his family’s downfall, making bad choices that has thwarted them every step of the way. Filled with complexity, depth, and sparkling dialogue, Miller’s masterpiece feels as fresh and relevant as ever.